rafx

Rendering Concepts

This is a quick conceptual summary of how most GPU-based rendering works

Some good resources:

- https://personal.ntu.edu.sg/ehchua/programming/opengl/CG_BasicsTheory.html

- https://alain.xyz/blog/comparison-of-modern-graphics-apis

When using a GPU there are three objectives:

- Initialize the device/window

- Load assets into GPU memory

- Draw on images and present them on the window

Initialization

The first step to rendering with the GPU is to initialize a device. Some APIs like vulkan have multiple things to

initialize like a VkInstance and VkDevice. Other APIs like metal just have a single object like MTLDevice.

The main objective here is to choose what GPU to use (it’s not uncommon to have two - for example, most intel systems with graphics cards!), get info about it (for example, what formats are supported or how far apart textures need to be spaced in memory).

For the most part, this initialization is boiler plate that rafx can do for you. See

RafxApiandRafxDevice

Buffers and Images

Fundamentally, the GPU has two kinds of resources to manage: “buffers” and “images”.

Example uses of buffers:

- Vertex Buffer

- Index Buffer

- Buffer used to store image data to be copied into a texture

Example uses of images:

- A read-only texture authored by an artist

- A swapchain image

- An image that is drawn to (sometimes called a “render target”)

Working with GPUs can quickly become overwhelming and daunting, so I think it’s helpful to know that ultimately, you’re only dealing with two kinds of resources!

See

RafxBufferandRafxTexture

Memory

There are two common cases for memory - an integrated GPU where the CPU/GPU share a pool of memory, or a dedicated GPU that has its own separate pool of memory.

Dedicated GPUs

When a dedicated pool of memory is available, there is generally some additional memory set aside that both the CPU and the GPU can read. Typically, the CPU will write data into this shared space and issue a command to the GPU to copy the data from that shared pool into on-GPU memory. (This memory is not visible to the CPU). Buffers used in this way are commonly called “staging buffers.”

Some resources only get used once (like a vertex buffer that is used to draw imgui windows). In those cases, it often doesn’t make sense to copy it from the shared pool of memory into dedicated memory - it can be used directly from the shared pool of memory.

Integrated GPUs

Integrated GPUs (which usually includes mobile devices and consoles!) often share a single pool of memory between the CPU and GPU. In this case, there is no need for staging buffers as the CPU. Sometimes this is referred to as “unified memory architecture.”

Queues and Commands

In order to tell the graphics card what to do, you must submit command buffers to queues. Depending on the hardware and API, there may be different types of queues that support different operations. Usually there is a “graphics” queue that supports all operations. It’s common to just have a single queue per type (even in shipping AAA games.) In fact, using more queues can be counterproductive if the card’s hardware just gets divided between them.

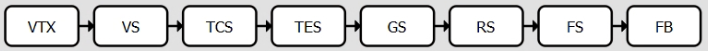

When work is submitted to the GPU, each unit of work goes through many stages. Depending on what work is being done, some stages will be skipped.

Every unit of work will go through these stages in the pre-defined stage order.

A second unit of work in the same queue does not wait for a first unit of work to execute ALL stages. For example, if the first unit of work is in the “FS” stage as illustrated above (fragment shading) the second stage of work is free to execute all stages up to and including the “RS” stage (rasterization).

See

RafxQueue,RafxCommandPool, andRafxCommandBuffer

Hazards

This can present a problem. For example, if a renderpass that writes to an image is submitted before a second pass that reads that image, it’s possible that the second pass’s read operation could occur before the first pass’s write operation. (Because the read operation is in an earlier stage than the write operation.) This can cause undefined behavior.

Most APIs have the concept of “pipeline barriers” or “execution barriers” that can would allow you to block the second pass’s read operation until the first pass’s write operation completes. There are often several mechanism to accomplish this synchronization that carry different trade-offs of overhead and flexibility. However, the details vary between APIs and are out of scope of this document.

In addition, GPU memory layout is usually not “coherent”. This means that a write operation performed in one stage may not be immediately visible to another stage. That writing stage must flush the modified memory from cache, and the reading stage must invalidate its cache to read the flushed data.

Older GPU APIs would handle hazards for you automatically, but the trend has been to move this logic into applications. This makes the performance implications of these hazards more visible to developers. It also allows developers who may know what operations they will be doing later to handle these hazards more efficiently.

However, dealing with these hazards is complicated, error prone, and unforgiving. In recent years, many applications have moved to “render graphs” - a way of describing units of work with read/write dependencies. This allows better synchronization than a driver could provide while limiting the complexity.

See

RafxFenceandRafxSemaphore. Also see therafx::graphmodule for a provided render graph implementation.

Swapchain Handling

Most applications that use the GPU follow a standard pattern of rotating through 3 images:

- The frame that is on the screen

- A frame that’s finished rendering and will be placed on the screen at the next vsync

- An incomplete frame that is being drawn

These three images are created by the “swapchain”. Because applications usually render to a window in an operating system, these images need to be in a format/size that the OS “window compositer” expects.

Sometimes the swapchain can become invalid - for example if a window is resized. In this case, the app must create a new swapchain.

See

RafxSwapchainandRafxSwapchainHelper

Pipelines

A pipeline represents the complete configuration for stages. Some of this configuration is “programmable” - meaning you can write shaders that execute on the GPU. (for example, vertex shaders and fragment shaders). Some of the configuration is “fixed function” - meaning you pick the pre-defined behavior you want by setting parameters.

Creating a pipeline is an expensive operation. It is almost like having to compile code at runtime. (Your shader will be translated into assembly instructions that the GPU can natively execute).

Pipelines are “bound” on a command buffer. This means that any draw calls recorded to that command buffer will run through the bound pipeline (until a different pipeline is bound.) Switching pipelines is not free so if it’s possible to batch draw calls that use the same pipeline together, it can sometimes be a win. However, sometimes the draw order is important and batching is not possible.

See

RafxPipelineandRafxRootSignature. (The root signature is analogous to DirectX root signatures and vulkan pipeline layouts.)

Shaders

GPU APIs usually require shaders to be written in a custom language for that API. DirectX uses HLSL, Metal uses MSL, and OpenGL/Vulkan (usually) use GLSL. However there has been movement towards having a single IR-like binary encoding (like SPIR-V) that may allow for more flexibility in the future.

For now, one of the most popular ways to handle this is

SPIRV-cross. It can read source code written in one

language (like HLSL and GLSL) and output source code for a different language (like MSL). In fact,

this tool is bundled with MoltenVK, a popular translation layer that allows running vulkan on apple

platforms by translating vulkan API calls to metal API calls at runtime. (gfx-hal/webgpu do this

too, but they are working on an alternative, naga)

There are also some projects like rust-gpu to write shaders

in rust, but they are very experimental at this point!

A point on terminology - phrases like “vertex shader” and “fragment shader” are common. However, these only represent on stage of a pipeline. Rafx uses the term “shader stage” in this case, and the term “shader” to represent all the stages that combine to create a pipeline.

See

RafxShaderModuleandRafxShader. Rafx provides a toolrafx-shader-processorthat usesspirv_crossto do shader translation for you ahead-of-time rather than at run-time.

Descriptor Sets

Once a shader is loaded, like any other program, it will take input, process it, and write output.

Some of this input comes in the form of bound objects (like vertex buffers and index buffers) and some of it comes in the form of descriptor sets. A descriptor set is like a pointer to a list of GPU resource. Grouping multiple resources into a single set allows them to be bound in a single operation. This is both efficient and convenient.

Descriptor Sets may contain many resources. It’s usually best to combine resources that change at the same “frequency” in the same set. So for example, if some resources are bound once per frame, and other resources are bound for each draw call, it would make sense to group those resources into two different sets by frequency.

See

RafxDescriptorSetArray. More details here: Resource Binding Model)

Render Passes

Renderpasses ultimately draw to one or more images. There are a few types of images that may be used. These images may also be called “attachments” - i.e. they are “attached” to the render pass.

- Color Attachments: Like it sounds, usually an RGB image. The image encoded in the RGB channels doensn’t have to be Red/Green/Blue. It could be other properties like a normal vector (xyz components) or material properties like roughness or specularity.

- Depth/Stencil Attachments: Most commonly if one is set, it’s just a depth texture (sometimes called Z-buffering)

- Resolve Attachments: Resolving generally means transitioning from MSAA to non-MSAA.

Modern GPU APIs allow you to control how/if these images are loaded/stored at the begin/end of a render pass.

See

RafxCommandBuffer

Draw Calls

With the pipeline, descriptor sets, vertex/index buffers, and render targets finally bound, we can finally issue draw calls! This is usually just a matter of specifying the range of a vertex/index buffer to use to draw.

Instancing is also available here for drawing the exact same thing many times, but there are restrictions on how it can be used.

See

RafxCommandBuffer